The wilderness, the untamed space between human settlements, plays an enormous role in the Bible. One entire book, the one that we today call Numbers in English, is titled Bemidbar, meaning “In the Wilderness” in Hebrew. It takes place entirely in the area between Egypt, the place from which Hebrew slaves fled, and the land that God promised in His covenant with the Israelites.

In our human-dominated biome, wilderness exists between constructs, whether they are gardens or cities or agricultural areas. Wilderness may be avoided, it may be explored, it may be traversed. In the Bible it serves as a place of refuge, of contemplation, of isolation, of passage, of rest, of conflict. In Leviticus, it is where the scapegoat is released, carrying away with it the sins of the Israelites. In the Gospels, it is the place where Jesus is tempted by the devil.

At times, it is the where humans make contact with God. It is where we are given the opportunity to grow, to see God’s intentions more clearly, to receive His instructions to us.

In Chapter 2 of Genesis, the second creation story, human life begins in a garden. Not in the wilds of nature, but in a defined place where nature is contained, tamed. We are told that God fills this garden with “every tree lovely to look at and good for food.” (We are told that this garden is “in the east” but the east of what is not made clear – we can surmise it is east of the Levant where the Israelite audience of the time lived. Geography is uncertain in this Biblical episode but the river Euphrates is named, which could suggest a Mesopotamian setting for Eden). I have spent a lot of time over the years thinking about gardens as an architectural element, and contrasting the garden with the wilderness, where nature is not cultivated and tamed, where things that may not be lovely to look at or good for food may thrive.

When Adam and Eve are expelled from the garden, they presumably are sent into the wilderness outside of the garden’s boundary, where God has told them life will be tough. It would appear that at this time, everyplace that was not Eden was wilderness.

After Adam and Eve settle again in this wilderness and bear two sons, the first murder occurs when Cain slays Abel. Like his parents before him, Cain is banished into the wilderness where, we are told, he and his offspring create cities and, presumably, civilizations that provide refuge from the surrounding wilderness.

The most elaborate and important wilderness story in the Bible is the aforementioned story of the Israelites’ journey from Egypt to Canaan, the Promised Land. This journey, which comprises the last four books of the Torah, is the foundation of both the state of Israel and the Jewish religion.

The five books of the Torah have a structure that may be diagrammed as A-B-C-B-A, where A – Genesis and Deuteronomy – are about the creation of the nation; B – Exodus and Numbers – are the stories of transit; and C is an internal climax, where God approaches the incipient nation most closely and gives it the structure and regulations needed for it to serve as His home on Earth.

Exodus and Numbers – or, to be more accurate, the first 60 percent or so of Exodus and the last two-thirds of Numbers – depict in great detail the human story of the Hebrews’ liberation from enslavement in Egypt and their 40-plus yearlong migration to the Promised Land. I stress that this is a human story, because so much of its contents reveal the mental and emotional state of the people as they make this arduous journey.

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, in his brilliant series of Torah commentaries,

Covenant & Conversation, brings in a notion from political science to help elucidate what is happening in the hearts and minds of the Hebrews. Sacks cites Ronald Heifitz’s theory of technical and adaptive challenges. Heifitz, a scholar at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, posits that these technical challenges are difficulties that can be resolved by external means – medicine to treat an illness, for example – while adaptive challenges require a person to change internally – a doctor’s recommendation to lose weight, exercise more, or alter one’s diet, for instance.

In Exodus, Sacks writes, we see multiple examples of technical challenges resolved via God’s intervention. The escaping slaves are trapped at the edge of the Red Sea; God instructs Moses to divide it to allow safe passage. When the Israelites have eaten all of the food they brought with them and complain of hunger, God provides manna from Heaven. When they are thirsty in the desert, God tells Moses how to draw water from a rock. This works quite well for the sojourners until they reach Mount Sinai, where God calls Moses to the mountaintop, leaving the people behind for 40 days.

Without Moses, who has been their intermediary with God, the people languish. In desperation for the presence of God, they talk Moses’s brother Aaron into making an idol, the golden calf, for them to worship. This of course, is a disaster, a pivotal event that changes the entire course of history. But it is the first time the Israelites have attempted to set their own course, solve their own problem. As wrong-headed as their solution was, it was the first time the people have tried to take hold of their destiny, to adapt to circumstances. How many of us have floundered terribly the first time we tried, unprepared, to solve a difficult problem?

In the Bible, the narrative is broken off at this point to focus on creating a religious structure – literally – to bring God close to the people. The last part of Exodus is devoted to the construction of the Tabernacle. The entire book of Leviticus details the rituals of worship as well as the religious calendar. And the first chapters of Numbers describe the people’s preparations to resume their travel.

In the rest of Numbers, the people face challenge after challenge, and Moses as their leader becomes frustrated, even distraught, at one point asking God to “just kill me.” These challenges are more difficult because they require the people to change. They must shake their slave mentality in which decisions were made for them, and learn to become self-directed.

In response to hardships, we see the people become nostalgic for their lives in captivity. Growing tired of their diet of manna, they long for life along the Nile, where at least they had fresh vegetables and fish to eat. They stage a rebellion and look to name a leader to take them back to Egypt. A team of scouts sent to scope out the Promised Land comes back and reports that it is inhabited by fearsome giants who will surely defeat them in battle. Even Moses’s siblings turn against him at one point.

God ultimately realizes that the people are not ready to become free and shape their own destiny. It will take generational change, and so He tells the people that those who fled Egypt will not enter the Promised Land. Only the next generation will do so, led by Joshua and Caleb, the only two of the scouts who gave an honest report about the current population of Canaan. God sets them wandering in the wilderness for 40 years.

The point of all this, in Sacks’ analysis, is that adaptive change takes time. Self-transformation is not easy. And once again I am staggered by the brilliance of the Bible in elucidating the intricacies of the human mind.

In this light I would like to look at the figure of Hagar, whose story is related in Genesis 16 and 21. She is an Egyptian and a slave, who works as a handmaid to Sarai, the wife of Abram. We are not told how Abram and Sarai acquired her, although one might speculate that the couple picked her up when they traveled to Egypt to escape a famine in the Levant. We don’t know how old she is, or what she looked like. She clearly is still in her child-bearing years, and is in some favor with her mistress, who selects her to bear a child for her husband, a child the mistress has grown to old to produce. But that’s about it.

Because the Bible reveals so little about Hagar, her “back story” has been filled in by numerous other writers. Some rabbinical sources have speculated that she was actually an Egyptian princess, given to Abram and Sarai by the Pharoah whose hospitality Abram and Sarai enjoyed until the king found out that they had lied about being brother and sister rather than husband and wife (they later are revealed to be half-siblings).

One Islamic tradition holds that she was the daughter of an early prophet.

But let’s focus on what the Bible actually says about Hagar.

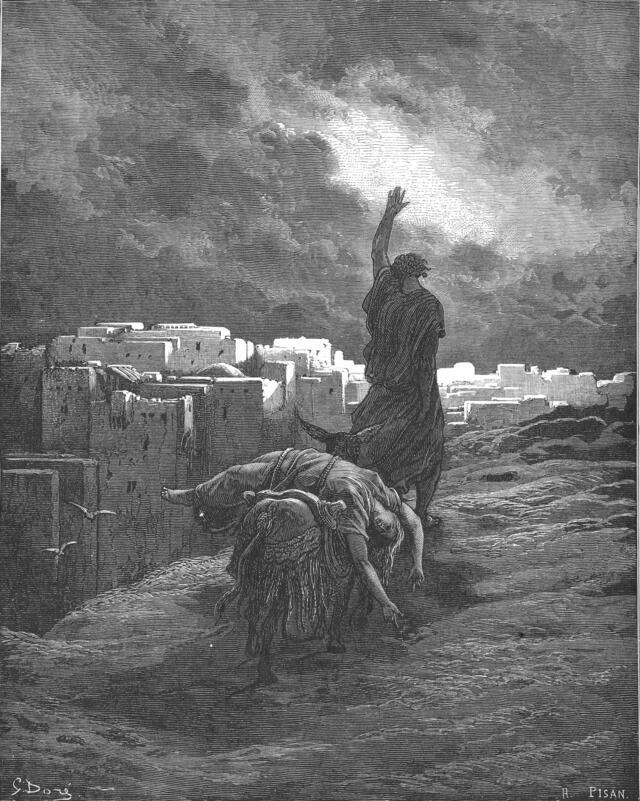

Twice, in Genesis 16 and 21, she is found by God in the wilderness. The first time, she is pregnant by her master, Abram, and has fled due to abusive treatment from her mistress. Sarai’s complaint is that now that she is pregnant, Hagar “looks down” on Sarai. Sarai goes off on Abram, blaming him for the situation even thought it was Sarai herself who engineered the coupling. Abram takes the passive route, telling Sarai she is free to do as she pleases with the slave girl.

The second time, Sarah (God has given her a new name by now) has succeeded in convincing Abraham to drive Hagar and her son, Ishmael, away, so that there can be no question about who will be Abraham’s heir.

Hagar addresses God using a name that occurs nowhere else in the Bible: El Roi, the God who sees me. That’s a fascinating detail, coming from a slave who, despite having been impregnated by her master, is essentially not seen as human. Sarai and Abram determine her fate without her input or her consent. The child she is to bear is expected to be raised as the child of Abram and Sarai, not of Hagar. It is only her hostility that draws attention – and that is suspect, given the way Sarai also lashes out at Abram over the results of Sarai’s own scheming.

One of the things that distinguishes the Judeo-Christian God is His focus on the weak and the poor, a characteristic also strongly present in the Islamic tradition. Hagar is not held up as a heroine in the Bible, although she is in Islamic tradition.

It is not surprising, in light of all this, that Hagar has become a revered and much-studied figure in African-American womanist theology (see

Sisters in the Wilderness: The Challenge of Womanist God-Talk, by Delores S. Williams). Williams writes of Hagar’s encounters with God:

“The two times that God relates directly to Hagar are in the context of helping her come to see the strategies she must use to save her life and her child’s life. The first strategy is to go back to her oppressor and make use of the oppressor’s resources. The second survival strategy not only has to do with the woman and child (family) depending upon God to provide when absolutely no other provision is visible, but also includes, upon God’s command, the woman Hagar lifting up her child and “holding him fast with your hand.”

In other words, Hagar is told that she must change in order to survive and to realize her potential and that of her son.

God promises to “make him (Ishmael) a great nation.” But in order for that to happen, Hagar must develop the survival skills to keep herself and her son alive in the wilderness. When she does so, we are told that Hagar raises Ishmael and secures him an Egyptian wife. No more is heard from them until Ishmael returns to Canaan for his father’s burial.

Two great nations, Israel and Arabia, survive to this day. Arguably, both exist because their founders were able to adapt.