A footnote in Robert Alter’s masterful translation of the Hebrew Bible referenced what I saw as an unlikely title: Leviticus as Literature, by the British anthropologist Mary Douglas. I have thought about Leviticus as many things over the years – a book of laws and regulations, a guide to proper living as a Jew (at least an ancient one), the source of much of the repellant weaponization of the Bible that we are forced to deal with in today’s society – but literature would not have been one of the ways I would have characterized the third book of the Torah.

Coming after the stirring narratives of Genesis and the first half of Exodus, the second half of Exodus and Leviticus together are like stumbling blocks put in the way of enjoyment of the Bible. Exodus’s long, detailed instructions on construction of every detailed aspect of the Tabernacle at least captured the part of my attention that has always drawn me to architecture and woodworking. I have sometimes wanted to try to follow these instructions to see what would result. But Leviticus has been a book I have had to force myself to slog through; I recognized its importance in the history of the Jewish people, but have found little in its repetitive instructions for animal sacrifice and priestly ritual, or its strictures regarding sexual behavior and other human interactions, to hold my attention. It has seemed the most ancient of books, and the least relevant to modern life. So this unexpected title intrigued me.

When I read -- especially when I read the Bible -- I follow trails of footnotes as a detective might follow clues in solving a mystery. One reference often leads me to another, and pretty soon I have accumulated a reading list that I may or may not be inclined to tackle. This footnote sent me straight to Amazon, where I found this 1999 title available as a Kindle book.

Thus I got my hands on a book that has had a greater impact on my reading of the Bible than any since John Shelby Spong’s The Fourth Gospel a decade ago.

Douglas approaches Leviticus as a cultural artifact rather than as a holy object. She situates it in its time and place – the Middle East, probably at the end of the Babylonian exile, when the author we refer to as the Priestly writer was active. (The Priestly writer also is credited with the first creation story, In Genesis chapter 1).

Douglas expends much effort in contrasting Leviticus with Deuteronomy, which she sees as a work of rational, scientific, modern thought. Leviticus, by contrast, operates by analogy, a more ancient form of understanding than science. Although she briefly addresses the question of which writer was earlier – the Priestly writer or the Deuteronomist – she knows that would be an endless debate and instead focuses on the difference in perspective.

The fundamental analogy she sees at work in Leviticus is the structure of concentric circles, which are applied to Mount Sinai, to the Tabernacle and to the animal body. The innermost circle in all of these, in her analysis, is the dwelling place of God: The peak of the mountain (think of it as the center if looking down from above), the “Holy of Holies” in the Tabernacle, and the guts – the reproductive organs and the intestines – in the body. The latter may be difficult for us to comprehend. Douglas explains:

“Bashfulness apart, it is important to ask why the innards should be at the point of highest esteem, the position that corresponds to the holy of holies, instead of the face or head or heat to which we accord more honour. The question calls for difficult comparative psychography, but at least recall that there has always been in the Jewish culture a strong association between body and tabernacle in respect of fertility.“The Bible locates the emotions and thought in the innermost parts of the body; the loins are wrung with remorse or grief; the innermost part is scrutinized by God; compassion resides in the bowels … The temple was associated with the creation, and the creation with fertility, which implies that the innermost part of the tabernacle was a divine nuptial chamber. Even from complete ignorance of mysticism, the analogy of the inner sanctuary with the centre of creation is intelligible. It was fitting that the sanctuary was interpreted as depicting in a most tangible form the union between God and Israel.”

This central idea, the association of the tabernacle with “creation and … ‘abounding fruitfulness’,” should inform our reading of the entire book of Leviticus, Douglas contends.

“Deuteronomy distances God, he does not abide in the tabernacle, only his Name and the glory of it are present, whereas Leviticus and Numbers believe God to be present, close to his people at all times, and meeting with them in the tent of meeting.”

One mistake we make, Douglas says, is to view Leviticus as a laundry list of rules and regulations and not as an overall composition:

“Leviticus has been read in an itemized way, items of law corresponding to elements of morality, or to elements of narrative, or to elements of hygiene, but not to their place in an integral composition.”

For today’s readers, familiar with modern astronomy, the theory of concentric circles may bring to mind our understanding of the solar system, which after all of an interconnected systems of concentric circles in rotation and revolution.

Douglas extends the analogy linking Mount Sanai to the Tabernacle to the body to the book of Leviticus itself, comparing its first seven chapters, which focus on sacrifice, to the forecourt of the Tabernacle, where the entire community could gather and where the sacrificial rites took place. The next three chapters comprise a narrative leading up to God’s killing of Aaron’s sons Nadab and Abihu for a vaguely defined offense having to do with bringing “alien fire” toward His altar. Douglas sees these chapters as an analog to the screen that separates the forecourt of the Tabernacle from its interior, the sanctuary, which can be inhabited only by the priestly caste.

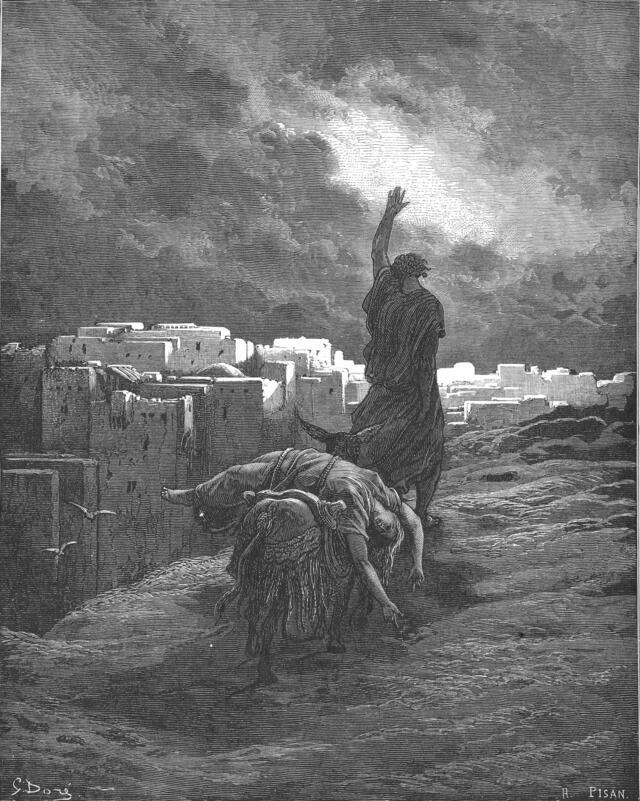

Douglas's diagram of Leviticus superimposed on the plan of the Tabernacle

Although these chapters bring us to the first screen, Douglas contends that the next 6 chapters, which give us the series of law, regulations and strictures regarding food; bodily emissions, including both sexual fluids and blood; and diseases of the skin, continue a circuit around the forecourt. Chapter 16 provides detailed instructions for the preparation that Aaron must make before entering the sacred space where the ark presides. And in chapter 17, we get a more explicit prohibition on the slaughter of animals in any context except sacrifice, as well as the rationale for the high degree of concern – she calls it squeamishness -- over blood. From Leviticus chapter 17:

“The life of the flesh is in the blood … for it is the blood that ransoms in exchange for life. Therefore, have I said to the Israelites: no living person among you shall consume blood, nor shall the sojourner who sojourns in your midst consume blood.”

With chapter 18 and its delineation of prohibited sexual practices, we move into the sanctuary, where we stay through the middle of chapter 24. In these chapters we learn, among other things, about righteous living, first for the people and then for the priestly caste; the importance of using only “unblemished” livestock in the sacrifice as well as the importance of human cleanliness in these situations; and the holy calendar.

In chapter 24, we get the second piece of storytelling in Leviticus, the story of the man who curses God and is stoned by the people. Douglas sees this as analogous to the second screen, the one that separates the interior of the Tabernacle from the Holy of Holies, where the Ark of the Covenant resides, and where only the high priest may enter, on only the holiest of occasions. Finally in chapters 25-27, we are in the Holy of Holies, where we learn about the Jubilee to be celebrated every 50 years, when debts are forgiven, slaves are freed, and the world is “reset” to one of equality for humanity.

Unlike the narrative books of the Bible, which are grounded in time, Leviticus is grounded in space. Reading it as a whole, we move deeper into the Tabernacle until we reach its most holy space. The importance of the narrative components as screen is that they serve as barriers to the next chamber. In Douglas’s words: “They are warning clear enough against sacrilegious approach.”

Given the climactic importance of the Jubilee, it may strike us as odd that instead of this celebration and return to equality lasting through history, it has been abandoned while the strictures on sexual behaviors have been so thoroughly weaponized that they have informed public policy in many places. By carefully reading and digesting Leviticus, one might get the idea that the “radical socialists” have it right, while the tsk-tsking church ladies and gentlemen are focused on less serious matters. Oh, well. That’s human nature for you.

Like many commentators, Douglas identifies chapters 18-20 as the “heart” of the book, with the two chapters identifying sexual offenses and their penalties framing a chapter on righteous living. Here is what Douglas has to say about that structure:

“There could not be a stronger framing of the central chapter at the apex of the pediment. Leviticus’ scheme very deliberately puts the laws of righteous and honest dealings at the centre and the sexual sins at the periphery. Less a pedimental composition, these two chapers are more like two massively carved pillars on either side of a shrine, or like a proscenium arch.”

Noting that this structure is introduced by a passage cautioning that, “You shall not do as they do in the land of Egypt, where you dwelt, and you shall not do as they do in the land of Canaan, to which I am bringing you,” Douglas sees the entire structure as one leading away from the idolatrous Egyptian and Canaanite cultures, which indeed were known for incest, in the case of Egypt, and temple prostitution, both heterosexual and homosexual, in the case of Canaan. Douglas summarizes it this way: “These chapters contrast the pure and noble character of the Hebrew God with the libidinous customs of the very strange false gods.”

Douglas’s innovative and insightful reading of Leviticus gives us new perspective on many of the familiar prohibitions, but perhaps none is more startling than her take on animal life. Connecting Leviticus back to Genesis, she reminds us that God created all of the creatures, and pronounced there that all of his creations were “good.” Keeping that in mind, she argues that conventional readings misinterpret many of the words and practices detailed throughout Leviticus.

She urges us, for example, to disassociate the emotions of disgust and revulsion from the term “unclean,” which she argues is a technical term related to inappropriateness for the temple, applied to menstruating women and men who have had wet dreams as well as to certain animals. Again, she notes differences between the ways Leviticus and Deuteronomy use words such as “unclean,” “impure,” and “abomination,” this last of which she sees as applying (in Leviticus) to the act of consumption rather than to the animal under discussion.

Douglas’s take on prohibition grows most interesting when she discusses the “swarming” creatures whose consumption is prohibited. These she sees as prolific breeders exemplifying God’s command to be fruitful and multiply. She also notes that many of these have few natural defenses, so that the prohibition on killing and eating them may be a way of protecting them and allowing them to thrive.

On the other hand, she is pretty much mystified about the ban on consumption of pork – arguably the most famous and widely heeded food proscription, detailing a variety of hypotheses without really coming to a satisfactory explanation.

While connecting the practice of sacrifice itself to the milieu of the ancient Middle East where sacrifice was endemic, she contends that sacrifice is a moment at the border between life and death where the animal is both killed and honored. The details of the butchering and the order of placement on the sacrificial altar is critically analogous to the three levels of Mount Sinai and the Tabernacle. The ban on killing and consumption of land animals outside the sacrificial setting – an important distinction from Deuteronomy – is testament to the reverence for the life of God’s creations.

In a fresh take on the ritual of the scapegoat, described in chapter 16, Douglas points out that while conventional readings suggest that the scapegoat is sent out into a fearsome wilderness where it will surely become prey and suffer an awful death, Leviticus itself makes no such prediction. It simply says that the scapegoat is sent away; it does not at all suggest a fate, positive or negative. It is God’s creature, not punished but set free, released into God’s wilderness, just as its partner, the sacrificial goat, is turned to smoke – which Douglas sees as transformation rather than destruction – allowing it to rise to God.

This essay could go on and on, becoming like Lewis Carroll’s ever more detailed map that ends up recreating the landscape it sets out to describe. To avoid that, I’ll stop here. I’ll save Douglas’s insights on skin and penetration (both sexual and not) for another time. But in resting, I hope that I have provided a reason for others to open this remarkable book and develop and understanding that moves beyond the widespread weaponization of some of its messages.